Eggstone Platter, 2010.

The celebration of Spring is thought to be one of the oldest cultural rituals. These Spring celebrations often include dyeing eggs. Eggs are the symbol for rebirth, renewal of life and the possibility for growth. Colored eggs were offered to the goddess Easter during the Vernal Equinox. The dyed eggs were often placed on graves as a charm or symbol of rebirth.

The word Easter is derived from the ancient word “eastre”, meaning spring. The goddess Easter/Oestre celebrates the Vernal Equinox, representing the sunrise, springtime, fertility and renewal of life. The Vernal Equinox is the transition from the dormancy of Winter to the life giving fertile season of Spring.

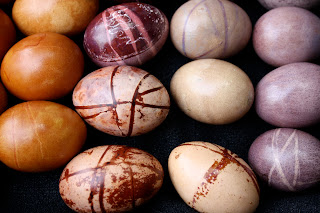

Eggstones, various colors, 2009.

Dyeing eggs is a fun activity. Each egg is unpredictable in its own marks, mottles, smears, lines and spots (thank you chickens) which are further enhanced by our intentional and serendipitous marks. Natural dyes create a harmonious palette, complimenting any Spring celebration. Most natural dyes used to color eggs are common pantry ingredients, including spices, foods, wines, flowers, and teas. Dyeing eggs during Spring is festive, cheerful and colorful!

Grid of Colored Eggs, 2009.

Common Easter egg dye is a form of synthetic food coloring. The chemical that does the dyeing is a molecule which gives the dye its color and bonds it to the eggshell. These now “traditional” egg dyes are rather garish in their colors. But, using natural sources to dye eggs offers many color possibilities and combinations.

Logwood and Red Wine Eggstones, 2009.

Logwood purple, fustic and quebracho red are tree sources, imparting soft or strong purples, golden yellow brown and pastel pink respectively. Cochineal is the time honored red dye derived from cochineal insects but on eggs creates a pale pink or a deep eggplant. Derived from the roots of the madder plant, eggs dye a deep brown with a reddish cast. Pomegranate is derived from the rinds of pomegranate fruits, casting an olive hint in its yellow hue. Green tea makes a clear light lemon yellow and black tea is deceivingly wood like in its appearance. Red cabbage transitions to various shades of blue in a cold soak. Coffee makes a light mocha and chamomile tea a lovely tan. Red wine's mysterious crystalizing effect adds sparkle. Turmeric and curry create a range of mellow yellows. Double dipping creates very unusual colors.

Eggstones (cochineal, logwood), 2008.

Various egg preparations expand the range of color from a single dye. Wash and rinse eggs well to remove any oils and residues. For long term use, either blow out the eggs or hard boil for a minimum of two hours. Allow the hard boiled eggs to continue to “dry out” after they are dyed. Eventually, you will be able to gently shake the egg and hear the dried yolk inside. Eggs can be boiled in water or in a water/white vinegar solution. Vinegar removes the outer membrane of the egg, giving some dyes a dramatic color shift, such as cochineal & logwood purple. Let the eggs cool in the pan, gently extract and rinse, and place on a towel to air dry. Make sure not to change temperatures suddenly.

Shibori Eggstones, 2009.

Some mark making supplies include rubber bands, nylon stockings for holding things in place, electrical or masking tape, beeswax & tjaunting tool, crayons, lace, fresh grasses, flowers and leaves or whatever else you can think of. Additional color variations can be achieved by varying the dyeing time. When an egg is placed in a dye solution, the dye bonds itself to the eggshell. When the dye is more concentrated or the egg is left to soak for a longer time, more dye bonds to the egg, resulting in a deeper color. Dyeing eggs with natural dyes usually requires extended soaking times.

Onion Skins boiling with eggs, 2010.

Some dyestuffs require boiling such as brazilwood, red cabbage or onion skins. Generally, boil the dye stuff material about thirty minutes and allow to cool. Either strain the liquid or leave dye stuff in the bowl and place eggs in the container. The cold dip method is convenient for extended soaking times. Gently lift eggs out of bowl with slotted spoon, tap dry with a towel so the dye does not “pull” on the drying rack, leaving a ring at the base of the egg. Some dyes may rub off more easily than others.

Boiled Red Cabbage, 2009.

Once the eggs are thoroughly dry they can be brushed with mineral oil. I love this process because the mineral oil brings out the natural colors and imparts a lovely sheen to the egg. For me this is the point when the eggs transition to EGGSTONES. They become even more mystical in their various shapes and color.

Eggstones, 2009.

Mineral oil does not go rancid like vegetable oils. But, I have applied mineral oil to freshly hard-boiled eggs only to discover the mineral oil blistering because the egg was still sweating; so be sure the eggs are thoroughly dried before applying it. The natural colored eggs can be stored in paper egg cartons in a cool, dark place. Eggs will continue drying so it is important not to store them in plastic.

Blue Speckled Egg (red cabbage), 2009.

Blues: Red Cabbage Leaves (boiled & cooled), Purple Grape Juice

Browns & Beige & Mocha: Strong Coffee (light mocha), Instant Coffee, Black Walnut Shells (boiled), Black Tea Leaves, Dill Seeds, Chili Powder, Chamomile Tea (lovely tan)

Greenish Yellow: Spinach Leaves (boiled), Liquid Chlorophyll

Grays and Lavender: Purple or red grape juice or beet juice, Red Wine (sit 24 hours-forms crystals), logwood purple

Orange Browns: Yellow Onion Skins (boiled), Carrots, Paprika, Madder Extract (deep chocolate w/vinegar eggs), Fustic liquid extract or shavings

Pink & Reds: Madder Root (long, slow cook), Beets, Juice from Pickled Beets, Quebracho Red Natural extract (soft pink), Cochineal (pale pink with baking soda), Brazilwood shavings

Violets & Purples & Eggplant: Red Onions Skins (boiled), Cochineal (distilled water, eggs boiled in water/vinegar), Logwood purple extract (deeper w/vinegar eggs)

Yellows: Carrot Tops (boiled), Green Tea (light lemon yellow), Ground Turmeric & Curry powder, Saffron, Marigolds, Pomegranate extract(olive cast).

Light Value Eggstones, 2009.

Egg & Nest is a beautiful book full of the unique marks that birds make on their own eggs:

Purcell, Rosamond, Hall, Linnea S., Corado, Rene. Egg & Nest. Belknap Press of Harvard, University Press, 2008.

Madder and Onion Skin Eggstones, 2010.